🎉 Gerry Scullion is writing a new book 'This is Human Centered Design' with BIS Publishers. Want to get early access, share your feedback, and submit a case study to be featured in the book?

In this episode, I caught up with a great friend of the podcast, Andy Polaine. Most of you will probably be familiar with Andy's work with Fjord and also as co-author of Service Design - from Insights to implementation on Rosenfeld Media, a book that has become one of the defining service design books over the last number of years.

I was hosting Service design Days in Barcelona this year and had lots of fun meeting the European service design community. It was a jam-packed few days for me but managed to capture some great conversations that all followed a similar theme to what myself and John Thackara covered in his episode recently, and that is, we need to consider not only what we produce but how we actually produce it.

Andy's keynote was fantastic and had some wonderful metaphors about how we have lost some of the natural cadence and craft through new work please like Agile and Lean.

Right, let's get into the episode.

Links from this episode

This transcript was created using the awesome, Descript. It may contain minor errors.

Gerry Scullion: 00:01 So here we are, Andy Polaine. A warm welcome

Andy Polaine: 00:04 Thank you. Nice to be here again.

Gerry Scullion: 00:07 You’re now at the top of the league for most appearances on the podcast. This is your third time. Yeah?

Andy Polaine: 00:12 I’ll strike that off my bucket list now.

Gerry Scullion: 00:15 Absolutely. So look, we’re coming from a Service Design Days conference in Barcelona and yesterday you gave the opening keynote, which was really well received here and it’s still being spoken about this morning. So, tell us a little bit about what you were. We were chatting about before about mindful services design.

Andy Polaine: 00:31 So it was, it was a talk around designing for the long-term or long-term thinking and mindfulness, and it’s kind of scratching my own itch in a way. I’ve seen a lot of the language around sort of sprints and MVPs and being fast to market and fail fast and move fast and break things has a place, but it’s also, it can get quite problematic if you, that’s all the only language you have, which just is, go as fast as we possibly can. Now for some things, it doesn’t matter so much if you make a mistake on something that’s not very important in life, but for services which are really part of the infrastructure of, of society. So that’s everything from you know, welfare and healthcare and you know, mobility and communications and so forth and you know, including social media when those things break or are designed without thought of the long-term consequences. That’s a real problem. Yeah. That starts having a kind of massive effect. And so my, my plea was really to have a cadence where you can go fast and it’s fine. And I had this metaphor of the four seasons of design, so you know it, in spring you’ve got the sort of early buds of an idea and at that point in time that the designer’s job is really also to kind of shield those early parts and being crushed by this. In summary, is going to launch time and everything’s going great and everything’s of slightly gets out of control and like my garden at home and then in autumn you start pairing stuff back, start repairing. Things started harvesting, we start to think about, you know, what, what’s happened here, and you start that process of reflection and in winter you stop. The nice thing about, at least in European, and Northern European winters is you’re, you’re forced to stop and you know, the garden itself. So there was a whole metaphor about gardens, but the garden itself as you know, withdraws and everything kind of dies back and there’s this moment of reflection and winter is traditionally a time of internal reflecting to us and my, it was more of a plea as much as anything, to say in a build this into your working life or your life in general, not just days, but weeks. Sprints. Just make sure there’s some of that time that you defend in order to have that kind of reflection.

Gerry Scullion: 02:37 Where do you think that the need for speed comes from?

Andy Polaine: 02:40 Part of it from Silicon Valley and startup movement, which is, you know, the, the classic and a hockey stick curve of growth, which is all about can you grow fast enough to disrupt the incumbent quicker than the incumbent can change, to, to defend against the disruption. And also before you run out of investment money and so there’s this sort of constant thing about getting faster to market, and digital has enabled that to be at speed, but what happens is the language around that and they kind of ways of thinking about that sort of perpetuate themselves. So you and I work in an industry where we’re designing stuff and there’s always the pressure to do it quicker and faster, quicker and so forth. In turn we expect all the tools and services that we use to be as quick as possible. You don’t have to wait what I have to wait a week to order something that’s outrageous, I should be able to get the next day and so forth. Which in turn you know, our expectations is someone else’s problem. We’re giving them less time. So, in general, we kind of perpetuate the cycle amongst ourselves.

Gerry Scullion: 03:43 So looking at the way people are currently working in all disciplines as regards to design and they might be in an organization that’s really urging them to work quicker. What would you say to them to take the message back to their boss and say, actually, you know what, we need to factor in the need for reflection, kind of what we’re doing.

Andy Polaine: 04:02 I know there’ll be plenty of designers in the audience saying “Well, that’s all very well”. That’s a nice idea, but you know, we just don’t have time for that. But that’s a bit like the whole sustainability argument of, wow, that’s great, but where’s the business case? For instance, there are things that you know, you have to do, and the same is true with time. You know, time is a, also a limited resource and you spend it where you deem important.

Andy Polaine: 04:25 And so if you say this thing is really important to me, then you prioritize it and that gets defended and you know, the same thing happens as soon as you have kids, for example, all of the things we said, well you know, I really have to stay late tonight to do this. That goes away, right? Just I’ve got to pick my kid up from school. I’m sorry I have to go. Everything else has to go around the immovable object…

Gerry Scullion: 04:43 …So that that need is, is equivalent to that in that metaphor.

Andy Polaine: 04:47 Well, I think you need to turn that space into an immovable object. Now. It doesn’t have to be massively disruptive either. And in general, it makes people much more productive, makes them, that gives them that extra time for the Polish of work, but part of it’s also thinking about where things that I’m kind of hanging onto process where you know, this is the way we have to do this and I can’t possibly move on to the next step until I’ve done this particular method or completed it in the way that I learned and so forth. That kind of dogmatism can easily become a kind of procrastination where we don’t want to move on to the next stage of synthesis or ideation, which is often the kind of psychologically a little bit of a kind of awkward stage sometimes or difficult stage of just one more interview and if I could just get one.

Gerry Scullion: 05:33 …You know the data better.

Andy Polaine: 05:35 Yeah. And it’s not just one more book from the library and I just, you know, it’s all actually kind of procrastination often and I think that, you know, you can, you can save time and then research is important. I really believe in it, but there are areas where you can save time and think, you know, I need to do that just enough because for me, the period of reflection or timeout is as important or more important than doing yet another kind of piece of whatever work I’m going to be doing.

Gerry Scullion: 06:01 So what do you say to people whose argument is that this is already included in the agile process? In the retrospective…

Andy Polaine: 06:08 It’s great, if it is and if it’s real. Sometimes I’ve seen those agile retros be, I’m quite sort of factory or lots of technical about it, you know, whatever kind of the validation Moore’s and know what we’re going to do next. Very macro. Yeah. And they, they are very sort of tactical and they work very well, but people are saying, you know, I’ve been feeling like this or I can’t keep working like that, or I really need to spend some time on there so I need to have kind of, you know, the emotional human side of things at that stuff also needs to come up to and being there. And I think that’s perhaps a difference between design and engineering and I don’t mean that in a dismissive way. I’ve talked to us culturally a difference between the sort of emotional space that designers often need and it’s just like a clear headspace or I’ve got a bit of time out to reflect and let that kind of process digest and work compared to some things. Much more of a kind of just moving forward onto the next bill.

Gerry Scullion: 07:03 So if you had, and you obviously can do at Fjord, you’re able to change the way you (as an organisation) are working and your role is in the Evolution team, what would it look like if you were to include this in the design process? Like, just to give it a bit more granular, clarity as regards when do you implement this and how often do you see it being implemented?

Andy Polaine: 07:23 I imagine that many of my colleagues would be listening to this and go, oh, come on Andy, you’re just making this up. You know, we’re working our asses off.

Gerry Scullion: 07:30 I’m sure they are. Yeah.

Andy Polaine: 07:31 And I’m sure they are. And so that was what the talk was really about and the reason why I called it about mindfulness because mindfulness isn’t necessarily about getting it right all the time. Mindfulness is about being aware, so if you can build it into the process. And so we’ve had to, I’ve had a team in Australia working on something and they had this, they did this thing called lion time and tiger time. Which I really liked and I don’t know if they’ve got this from somewhere else, but they had this thing where, um, you know, tigers hunt on their own, lions hunt in packs and so they would divide up the day and they’d say from this period of time this morning where we’re in entire time, got headphones on, concentrating on the stuff I need to do and then after lunch we’re going to have some lion time where we’re going to have discussions about things.

Gerry Scullion: 08:13 So you’re in a pack.

Andy Polaine: 08:15 Yeah. And you know, just being clear that that’s how the team’s going to work. And those also become sort of self-policing norms. So there’ll be other things were people saying, you know, you need to leave now, Gerry, because you told us that your yoga class is really important on Tuesday nights and you’re going to miss it. And so that kind of thing gives us a behavior or permission to actually look after yourself.

Gerry Scullion: 08:34 So it extends beyond the delivery of a service that extends to the employee experience and making sure that the wellbeing of the designer is actually being looked after.

Andy Polaine: 08:43 Yeah. And yeah, it is, and, and I think some of that though is, you know, it becomes a personal thing, but if it’s also the part of a tea and it becomes part of that kind of project process and you get those kind of behavioral norms and cultural norms of this is how projects work and then that becomes part of your process that some teams might go up, we don’t need this at all, we’re just going to power through because we’re so great and that’s fine if that works for them, but I have seen enough kind of sense of do you know, I just need a bit of space from, you know, not just for designers say within Fjord, but also in client teams and stuff with. It’s clear that there’s just too much going on and everyone kind of benefits from it just, it could just be a couple of hours. It could just be as disciplined as making sure you actually go out for lunch and don’t eat it at your desk.

Gerry Scullion: 09:24 I know like I, I gave a talk recently and I nicked a quote from Marshall McLuhan, which you reminded me of an one of the earlier podcasts. We shape our tools and therefore our tools shape us shapeless. Where do you think this approach fits in within like the, I guess the design thinking process and the ability to alternate and how that relates to design craft?

Andy Polaine: 09:46 I think one of the big misconceptions about design thinking is that the idea that the thinking happens upfront and then you just get on and do stuff and I think that’s happened because it’s still kind of seen in, in terms of a kind of industrial process that we’re planning and then we go into kind of manufacture …

Gerry Scullion: 10:05 which is like a waterfall approach anyway.

Andy Polaine: 10:06 Yeah. So whereas there’s any actually as one person knows, but certainly as any designer knows, that’s a third of the thinking. Most of the thinking’s happening whilst you’re doing. Yeah, and often you say, you know, as an example, if you’ve ever had to have a difficult conversation with someone, you had to break up with someone you’ve had to fire someone or, and you’ve lain awake all night going, so I’m going to say that and then she’s going to say this, they’re not going to say that and you know, it actually happens and as you open your mouth and it all just goes completely off the rails, it doesn’t go to plan at all. That happens a lot. Right? So you’re designing something and you realize, ah, we’ve designed it. Now I’ve actually made that tangible, uh, we’ve designed ourselves into a corner and I have to kind of rethink that or that brilliant idea. That was a kind of platonic ideal of an idea, as soon as it’s made real, it doesn’t make sense at all. Now I see it. That doesn’t make sense. Or those three things that I thought was separate and now one thing, all of that kind of reflective practices that Donald Schön stuff happens. whilst ‘you’re designing’ and there’s a whole process of kind of doing that goes.

Gerry Scullion: 11:06 And so all that hand to mind connection…

Andy Polaine: 11:08 Yeah. And you do need that and you know, that’s also a Donald Schön talked about you, you do need this kind of process of I’m to plan that kind of thing and then again to do some doing and are going to be doing some thinking with I’m doing and then I’m going to look at what I’ve done and thought about it. And then I’ll do some more doing and if you chance short circuit that too much. We’re doing it just doing, doing, doing and the lack of longterm thinking whilst you’re sprinting. I mean it’s like kind of running along just looking at your feet at some point you’re going to continue to hit the wall. Yeah. Yeah. So you need to look where you’re going.

Gerry Scullion: 11:37 It was a great story you told and I was definitely able to connect with the story. I remember the old days of when you used to use photoshop and you wish you’d add a blur. In my case, I was ‘zip file’ time. So yeah, it hit save and then I’d go to lunch (!) and then we come back from the Spar, that was next to NCAD where I studied, there’s a Spare shop up there, and I would literally be able to go the five minute walk down, get a roll, like a sandwich for anyone in America. I’m bringing it back, and it would just be in time to collect the saved file. But in that time I was able to, you know, reflect on what I was doing in work,. How can we incorporate that type of thinking into the day to day?

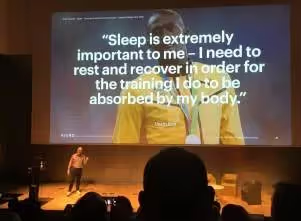

Andy Polaine: 12:14 So that goes back to the McLuhan quote, which is, you know, we have this thing of we shape our tools and thereafter they shape us that, you know, if you’ve got a tool, if you’re using a process or a tool that has some kind of enforced moment of kind of pause in it because you know, the progress bars is rendering, then you’re forced to kind of think about something. I used to read a book quite often and yet it’s often a book related to maybe what I was doing and it was John Warwicker from Tomato, who said, you know, I used to really like when computers were slow because I’d be able to think about things. You know, when you’ve got tools that are kind of incredibly fast and you just be honest, kind of work very, very quickly without any kind of enforced break of any kind. Then your tools shape your thinking and then if you start using language around sprinting and so forth, and again I’m not demonizing sprinting is a very good format, but what I’m saying is the language also sets up the mental model and all the kind of ways you think about that stuff and the reason why I put the Usain Bolt quote up there, the fastest man in the world and here’s the quote from him is about sleep and how important sleep is to him.

Gerry Scullion: 13:20 Absolutely. I remember when we caught up to other night, I was telling you the story about John Cleese who is a very famous member Monty Python. He was writing the script for faulty towers and he wrote it and then he lost it before you submit it to the BBC. And then, um, he was forced to rewrite us and then a number of years later when he’s going through a divorce, he found the first script and he saw that the first script that he written was not as good as the one that he rewritten with the second script. And he was, his argument was the subconscious worked in a time in the difference between the first script and the second script and was considerably better. So I guess I’m seeing those kinds of parallels between the stories in terms of being able to take that time to reflect. What role do you think and subconscious, I guess plays in the design process?

Andy Polaine: 14:06 I think there’s a massive role in that. And I get married to a psychotherapist, so, uh, but I think it’s also, you know, I always say I’ve done a lot of writing and these have a design column for a design magazine could Desktop in Australia and every month I’d have to turn out a thousand words. And I’ve also done long-form writing now with my book, and my PhD and stuff and with those things, the thing I really learned was, you do your planning, you’ve got to have an idea about what you want to write and then you do the writing and whilst you’re doing the writing you don’t do any editing at all. And that’s really important and that’s where they’re kind of raw material is coming out and you’re just letting yourself go. And there’s a great book called ‘writing down the bones’ by a woman called Natalie Goldberg and she, she talks about letting yourself, write shit, you really have to like the first three or four paragraphs, I’m, I’m literally having to override the inner editor saying going “this is rubbish” and go, yeah, yeah. And this is rubbish. And that’s okay.

Gerry Scullion: 14:59 Power through it.

Andy Polaine: 14:59 And then having done the writing and preferably with a little bit of time in between, you go back and you restructure and you edit and so you go, well in my writing went kind of off plan. But actually where I’ve gone to as much more interesting. So I’m going to restructure or my writing one of plan, I really need to edit that back to get it back to the structure, but that process of separating those two is really important because that’s how you avoid analysis paralysis. So if you’ve ever been a person who’s sat there for an hour writing the first paragraph or the first sentence of something you’ve had to write which is most of us, that’s what’s going on, right? You’re muddling those two processes up and I’m convinced it, those two need to be kept separate and that’s part of what I guess I’m arguing about with this.

Gerry Scullion: 15:40 I think that’s the nice way to wrap up the conversation. I’m going to put a link to the presentation in the show notes for anyone who wants to contact you, tell us how they might reach out to you.

Andy Polaine: 15:51 So I’m @apolaine almost everywhere, so a p o l a I n e dot on twitter. You’ll find me on LinkedIn and the podcast slack channel too…

Gerry Scullion: 16:00 …you drift in and out of the slack channel. You’re like an enigma.

Andy Polaine: 16:05 …just ‘@’ me in the slack channel. I have a bit of a discipline that’s actually a mindfulness thing, so I think it was one of these Tristen Harris things actually about time well spent, but I have a thing where I’m a policy about only set notifications from people not machines on my phone, so if it’s any kind of messaging thing that gets through, if it’s directed at me, if it’s just some kind of nudge from some app, it doesn’t come through, it’s turned off.

Gerry Scullion: 16:28 Might be another thing to be chat about in the podcast in the future. Andy great chatting to you again.

Andy Polaine: 16:32 Thank you. It’s lovely to be here.

Here's our last three episodes from This is HCD.